At social or family gatherings, I am often asked to name one person I would like to meet from the past. To be, candid, I’m never able to come up with a good answer. I usually default to one of my great grandparents I never had the privilege of knowing, or one of the famous classical composers whose works I daily enjoy: Mozart, Chopin, Beethoven. If I give it a bit more thought, I might come up with some who were important to the founding of America like George Washington or Patrick Henry. But I hate giving tired, boring answers to this question; I’d rather come up with someone original, who I’d genuinely want to meet yet someone lesser known who doesn’t get the attention they deserve. I’ve been giving the question a lot of thought recently, and I believe I can now offer a clear, singular answer that I don’t imagine many will duplicate: Woodes Rogers, the man who ended piracy in the Bahamas.

Postcard competition

Growing up in Nassau on New Providence, Bahamas, there seemed to be a countless number of pastimes to enjoy that were not accessible to most children. If I were to allow you a guess as to which was my favorite, I guarantee you wouldn’t succeed—I could even give you five guesses. Yes, I loved going out in the boat, shelling, fishing, diving conchs, gazing at exotic flora, watching hummingbirds feed on coral fountain plants, and swimming at beaches seemingly reserved for me and my family, but if I had to pick one pastime that had the biggest impact on me—that captured my imagination every day anew—it would be simply riding around the island and taking in the scenery that echoed stories of the past.

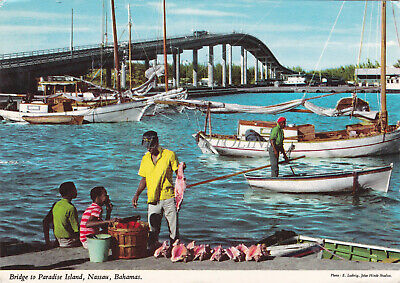

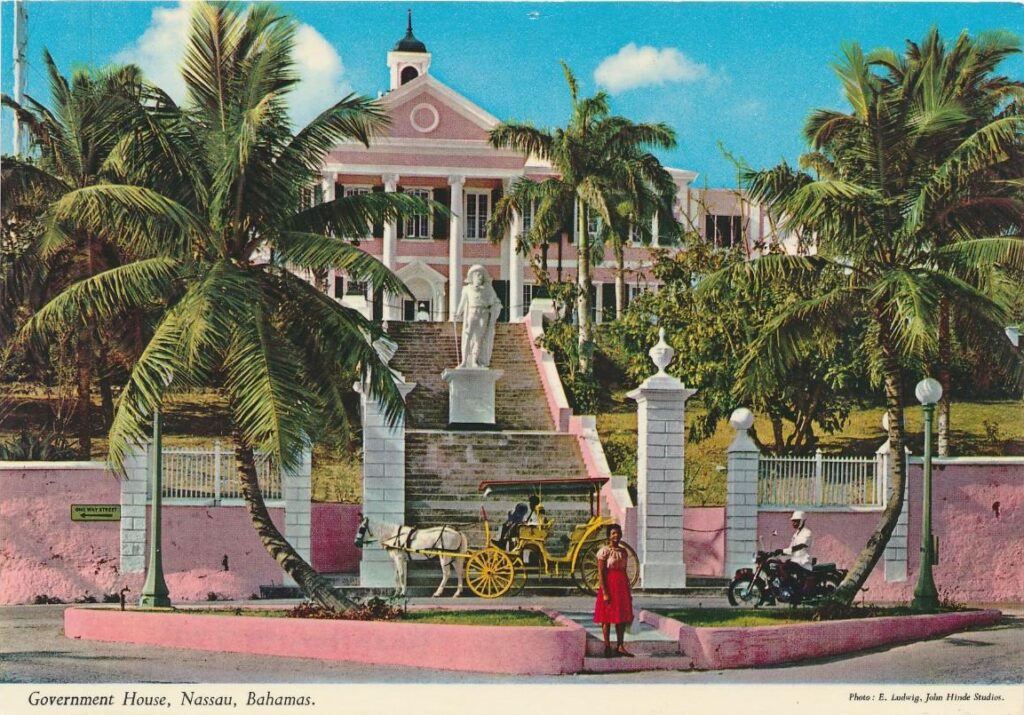

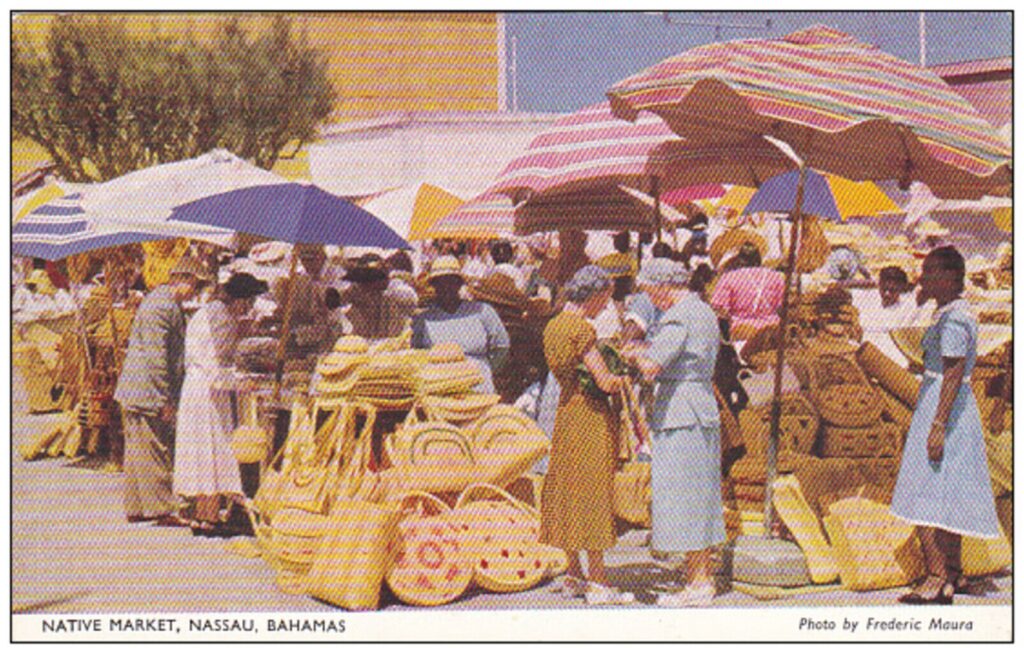

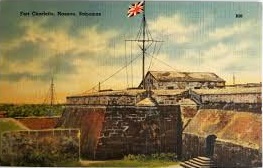

Most often going for a ride in Nassau meant traveling the prominent street that lined the bay, aptly named Bay Street. It meant I’d have the privilege to witness a presentation of views I never grew tired of: the long mound of discarded conchs shells along the harbor with its pink hues and ever-present stench everyone complained about; the bridge over the harbor connecting Nassau to Paradise Island where all the stories of my grandfather, Mertland Higgs, working as caretaker for the Porcupine Club, would come to life; the many hotels where my brothers and I would go swimming and mingle with tourists who would have no idea we were locals; boats at anchor in the harbor, preparing for their next trip, be it spearfishing, pulling fish traps, or diving conchs; the many historic buildings and homes in the design of quaint colonial Georgian architecture, arrayed in pastels and ornamented with quoins; Government House with a statue of Christopher Columbus overlooking the harbor; the hubbub of downtown Nassau and the Straw Market; and not far beyond downtown sat Fort Charlotte, the centuries-old limestone fort that carried with it all the lore of pirates and cannon fire. I guess you could say I lived a postcard life! But as fascinating as each of these sights were, there was yet another that topped them all. And again, you would never guess it.

Beyond the Straw Market, the pink edifice of the British Colonial Hotel signaled the one sight out of them all that stirred my imagination more than anything else: the statue of Woodes Rogers. There, larger than life, stood an imagined image of a man to whom the Bahamas, and much of the world, owed a great deal of gratitude, but alas was largely forgotten. Unless you have watched a TV series about Caribbean pirates and took note of an obscure side character, most people reading this would be saying “Woodes who?”

One glance at Rogers’s likeness I would be thrust into the early 1700s, into a Nassau ruled by pirates. I didn’t really know anything about Woodes Rogers, just what I’d been told: that he had rid the Bahamas of pirates, which was true; that he dueled with Black Beard, which was false. I have to credit my dad with the dueling Black Beard story—I think he might have even said he killed Black Beard, but I can’t recall.

My childish mind imagined Rogers’s statue drawing his sword for said duel, and it was only recently I noticed he was drawing a pistol and his sword was actually sticking out of his long coat, secured in its scabbard. Maybe my childish wonder desired so much to believe he was preparing to engage in swordplay with Black Beard that it overrode reality. The plaque below reads “Pirates expelled, commerce restored,” the English translation of the Latin motto adopted by Rogers and incorporated into the original colonial badge: Expulsis piratis restituta commercia.

But what about Mr. Rogers?

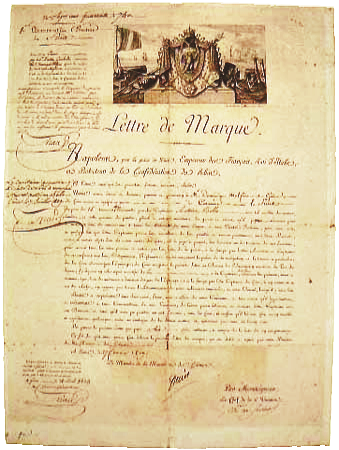

But who was this man with a unique name who so captured the mind of a young Bahamian boy? I learned early on he was the first royal governor of the Bahamas—which was significant in and of itself. Yes, there were governors before him, but he was the first one appointed by the King in official capacity. Before he was a governor, he was a privateer. I learned the difference between an English privateer and a pirate: perspective. To an Englishman, any mariner operating under letters of Marque on behalf of their motherland was a privateer and a hero; to nations at war with Great Britian whose ships were targeted by said mariner, they would be considered nothing but a thieving pirate. When the privateers failed to discriminate with their targets and attacked ships from their own country, they were out-and-out pirates to the world.

Rogers never violated his letters of marquee and stayed true to Great Britain. Born in 1679 to a seafaring family, saltwater ran through his veins. His maritime career coincided with the thickest part of the Golden Age of Piracy, and it was his actions that would bring about its end. We’re talking about the time where Nassau was considered a republic of pirates, where infamous pirates ruled such as Benjamin Hornigold, Olivier Levasseur, John “Calico Jack” Rackham, Henry Jennings, Sam Bellamy, Charles Vane, and Blackbeard. Rogers came to Nassau in a seven-boat flotilla (only four of which were vessels designed for battle) and little more than 400 militiamen. Keep in mind that Blackbeard alone was reported to have 700 men under his command. To say he was knowingly sailing into a situation where the odds were highly stacked against him would be a severe under-exaggeration.

Regardless of the odds, Rogers was successful in convincing the majority of the pirates to accept the king’s royal pardon. But not all the pirates were willing to lay down their arms like good little boys. Charles Vane, the most notorious anti-pardon pirate, scorned the offer of pardon, going so far as firing upon one of Rogers’s boats and then sending a fireship toward the flotilla. The fireship wasn’t successful in harming Roger’s fleet, but it did allow Vane to escape later in the morning out the other side of the harbor. But when months later Rogers hanged eight pirates outside Fort Nassau, piracy in the Bahamas received its deathblow.

A Man’s man

I imagine the decision by King George I to appoint the first royal governor of the Bahamas came with much serious deliberation. What kind of man would be appropriate to go into such a dangerous and volatile environment where others had already failed? What kind of man would dare go? Rogers’s reputation was established during his privateering career. During his most recent voyage, he proved he had the mettle to deal with great adversity: overcoming various mutinies, winning seemingly outmatched battles on the sea, dealing with debilitating sicknesses. But the biggest boost to his reputation came with the taking of the Manila galleon.

The Manila galleons were prime targets for privateers due to their promise of great fortune, but they were armed fortresses that made privateering vessels seem like nuisance flies to a bull. The only time the Manila had been captured was by Sir Thomas Cavendish in 1587, 122 years earlier. Rogers repeated the feat, but at a great price, taking a musket ball to the face that carried away part of his upper jaw and several teeth. As a result, he was forced to write out subsequent commands throughout the engagement due to pain and to prevent loss of blood. Unaffected by the thrill of success and undeterred by his wounds, Rogers set off to try capture the other Manila galleon that had separated from her consort. In that failed skirmish where Rogers’s party fired “not less than 500 shot in the galleon,” he experienced another crippling wound from a wood splinter sent flying by a cannon ball. In his words, “my heel bone being struck out and ankle cut above half through.” Though in great pain and bleeding badly, he refused to be taken below but continued his command, issuing orders from his back while lying on the main deck. The pirates of Nassau knew Rogers was not a man to be trifled with.

Does a picture paint a thousand words?

There are no Polaroids from Rogers’s day, so my mental image of what he looked like was shaped by that statue in front of the British Colonial Hotel. With only that to go by, I imagined him a fit man of average height with wavy, flowing hair, cavernous eyes, and a stern, stony visage—someone out of a Hollywood movie. But the only thing that can give us an idea of his physical likeness is a painting by William Hogarth. Here, donning a wig, he appears to be a man of imposing size yet with a gentle expression and a very present nose. Hogarth painted this after Rogers’s return to Nassau for his second stint as governor, though there is no indication of facial deformity. The man to his right, presumed to be his son William, holds a map of New Providence. What I always loved about this painting was how proud and satisfied Rogers seemed to sit. But all in all, this depiction looks nothing like the statue.

A man worthy of honor

Rogers went on to clean up and fortify Nassau as best one could with the lazy, drunken rabble left him, trying to mold them into a respectable people–he even brought religious pamphlets along with the king’s pardon in hopes of reforming the pirates. After spending thousands of his own pounds in contributing to Nassau’s revitalization, he returned to London after his first term as governor (1718-1721) in great debt, and they through him in debtor’s prison, forcing him to declare bankruptcy. Seven years later, he returned to serve a second stint as governor of the Bahamas (1728-1732), dying during his term in 1732.

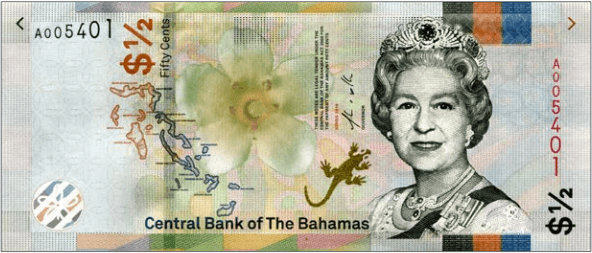

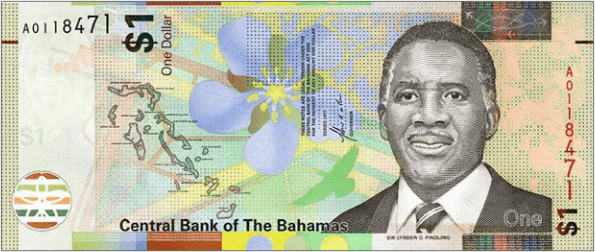

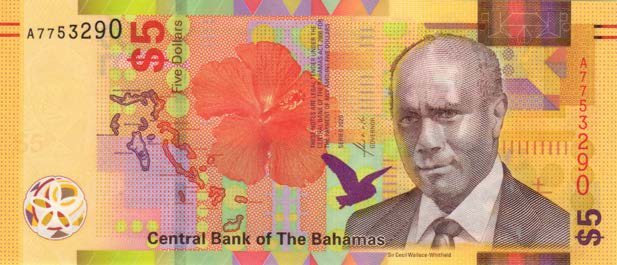

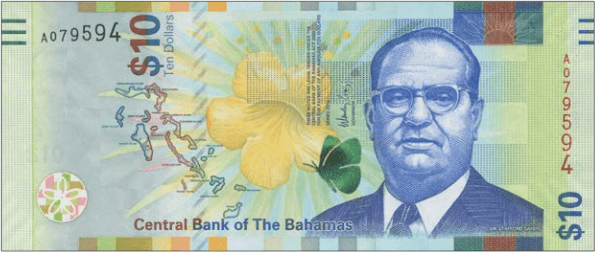

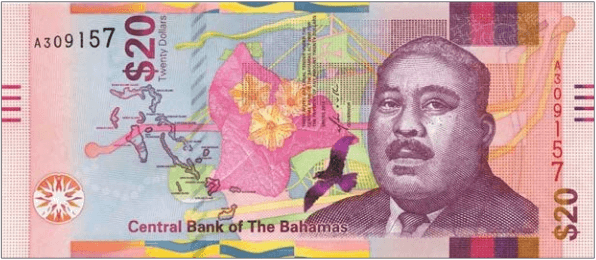

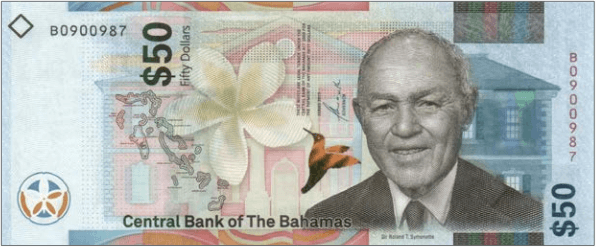

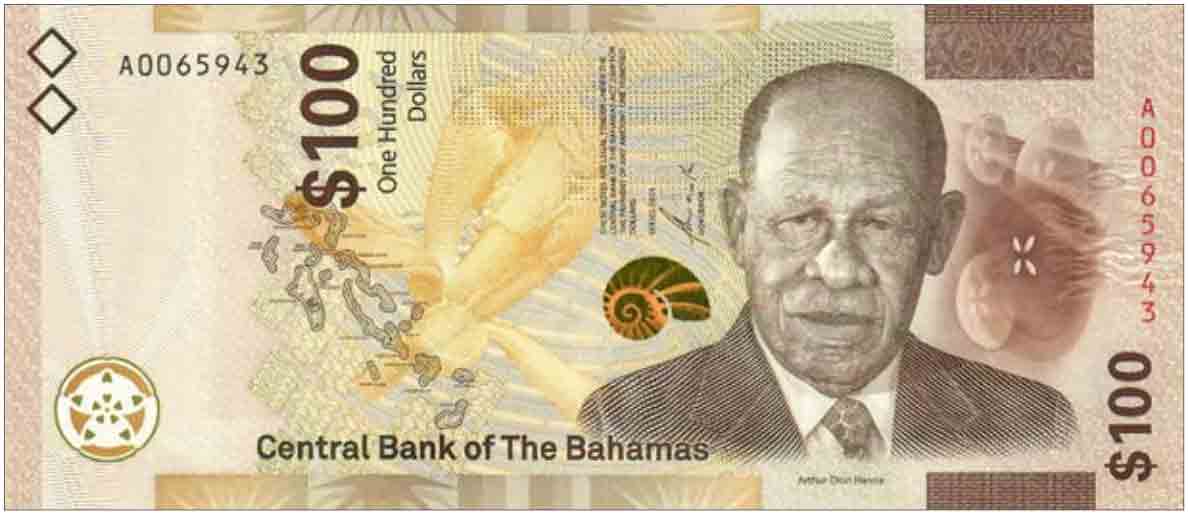

When the Bahamas changed their currency to replace Queen Elizabeth with men who made significant contributions to the Bahamas, I was surprised and a little disappointed they did not include Rogers. After all, there would be no Bahamas without Rogers’s sacrifice and his success in eradicating piracy. Yes, eventually someone—or a bunch of someones—would come along to do the job, but it was Rogers who did it. What greater impact could one man have had? Yet of all the opportunities to grace one of the new paper bills ($.50, $1, $3, $5, $10, $20, $50, $100), Rogers was denied the honor. Were his contributions insufficient? One might argue they chose to honor those whose contributions towards Bahamas’s independence (1973) and post-independence were the most significant, but Queen Elizabeth is there–twice! They should have included Rogers.

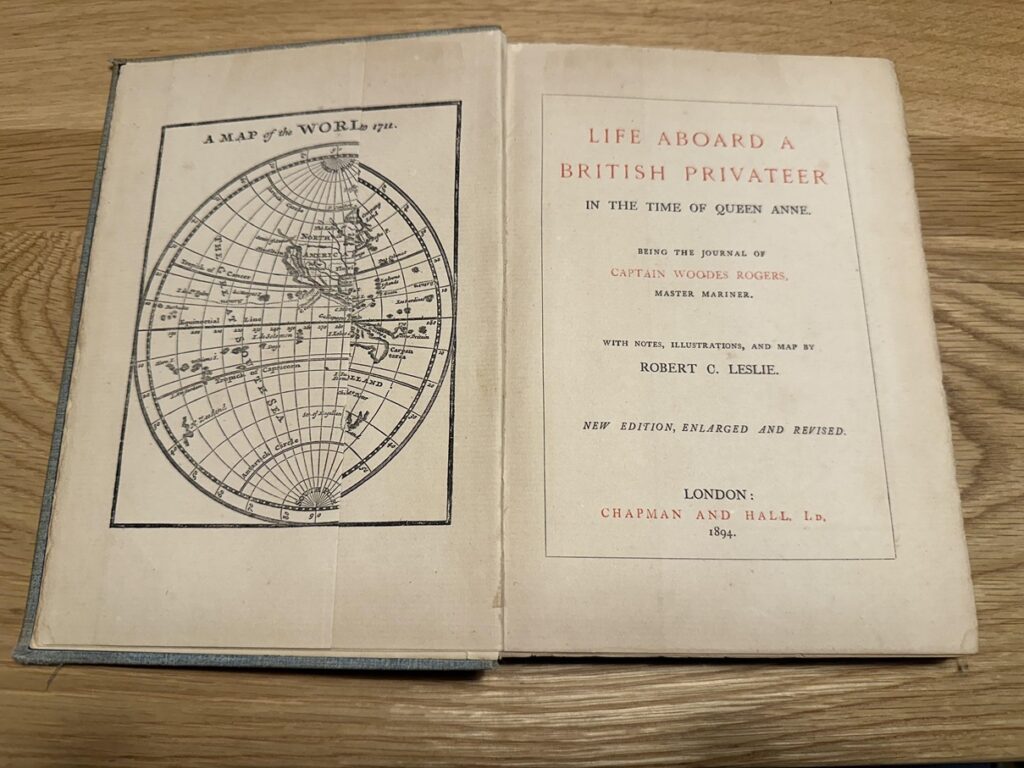

The quotes I’ve used in this post are taken from Rogers’s journal during his privateering voyage that netted the Manila galleon: Life Aboard a British Privateer in the Time of Queen Anne. An interesting sidenote from his journal is the rescue of a Scottish sailor from the Juan Fernandez islands who was marooned for four years and four months: Alexander Selkirk. Rogers brought him back to England and he became the inspiration for Daniel Defoe’s novel Robinson Crusoe. Rogers’s journal is one of my historical treasures. As you can see in the picture, the date of this reprint is 1894.

I hope one day the Bahamas will give Rogers some official recognition, even if only temporary like they did by printing Christopher Columbus’s likeness on the $1 quincentennial note in 1992. Just as Americans give honor and permanence in their minds to their forefathers, Woodes Rogers deserves nothing less from all Bahamians. Until the day he receives his due, I will at least do my part and make him my answer to a previously puzzling party question!

If you have visited the Bahamas, what was your favorite sight or pastime? What historical figure would you want to meet and why?